More Information

Submitted: November 01, 2021 | Approved: November 13, 2021 | Published: November 15, 2021

How to cite this article: Hossain MS, Islam A, Labony SS, Hossain MM, Alim MA, et al. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapeutic management of Dipylidium caninum (Cestoda: Dilepididae) infection in a domestic cat (Felis catus): a case report. Insights Vet Sci. 2021; 5: 024-025.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ivs.1001032

Copyright License: © 2021 Hossain MS, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Dipylidium caninum; Domestic cat; Niclosamide; Albendazole; Levamisole

Clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapeutic management of Dipylidium caninum (Cestoda: Dilepididae) infection in a domestic cat (Felis catus): a case report

Md. Shahadat Hossain1, Ausraful Islam1 , Sharmin Shahid Labony1, Md. Mokbul Hossain2, Md. Abdul Alim1 and Anisuzzaman1*

, Sharmin Shahid Labony1, Md. Mokbul Hossain2, Md. Abdul Alim1 and Anisuzzaman1*

1Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh

2Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh

*Address for Correspondence: Anisuz Zaman, Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh, Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Background: Dipylidium caninum, a zoonotic cyclophyllidean tapeworm, mainly infects dogs, cats, and occasionally humans as well. Here, we present D. caninum infection in a domestic cat. A cat of about one year of age with a history of intermittent diarrhea and shedding stool containing whitish cooked rice like soft particles.

Methods: The case was identified by thorough clinical, coprological, and parasitological examinations, and treated accordingly.

Results: During the physical examination, the cat was found to be infested with flea, and coprological investigation revealed the presence of gravid segments of cestodes. By preparing a permanent slide, we conducted a microscopic examination, and the cestode was confirmed as D. caninum. The cat was treated with albendazole and levamisole, which were ineffective; additionally, levamisole showed toxicity. Then, we administered niclosamide which completely cured the animal. On re-examination after a week, feces were found negative for eggs/gravid segments of any cestode.

Conclusion: Niclosamide was found effective against dipylidiasis and can be treated similar infections in pets.

Dipylidium caninum (Cestoda: Dilepididae) is an arthropod-borne zoonotic tape worm that is commonly known as dog tapeworm, flea tapeworm, double-pored tapeworm, or cucumber tapeworm, and it has a global distribution. The adult worm is about 46 cm long and mainly infects dogs and cats; however, it can also cause infection in humans [1]. It is primarily transmitted by fleas such as Ctenocephalides canis, C. felis, and Pulex irritans, and the dog biting louse, Trichodectes canis. Animals infected with D. caninum shed proglottids with feces, which rupture in the environment, releasing thousands of eggs. Developmental stages of flea and lice become infected through the consumption of eggs in which cysticercoids develop [2]. Cysticercoids become infective when the developmental stage of the flea moults to an adult and starts feeding on host’s blood. Usually, after ~36 h of a blood meal, the cysticercoid becomes infective inside the flea. Definitive hosts get the infection by accidentally ingesting infected flea or lice [2,3]. Adult worms live in the small intestine and can cause damage of tissues at the site of attachment, leading to the development of enteritis, diarrhea, and hemorrhages in the mucosal surface of the intestine. The infection is clinically manifested by retarded growth, weakness, loss of appetite, intermittent diarrhea, and shedding of whitish/creamy white segments with feces [3]. Humans, particularly children, become infected with the parasites by accidentally ingesting the infected flea containing viable cysticercoids while playing with dogs and cats [4,5]. Pruritus develops when gravid segments pass through the anus of the infected host. Here, we describe the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of Dipylidium caninum infection in a domestic cat.

A domestic cat (Felis catus) of about one year of age was presented to the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University with a history of dullness, inappetite, diarrhea, presence of creamy white cooked rice like soft materials in feces and loss of appetite. Additionally, the cat was heavily infested with flea and showed marked restlessness characterized by self-scratching and biting of body coat. The owner was using albendazole to dewarm the cat quarterly. There was no history of fever or vomiting. The cat had normal pink conjunctiva and was found healthy. Gross examination of feces showed the presence of gravid segments of some tapeworm(s). Therefore, segments were collected and processed for parasitological examinations. Gravid segments were separated from feces and kept in a normal saline solution. Under the stereoscope, gravid segments were found to have a cucumber seed shape. A gravid segment was fixed with a fixative containing alcohol, formalin, and acetic acid (AFA solution), stained with Semichon’s Carmine stain and examined under the microscope under an x10 objective by preparing permanent slides. After diagnosis, the cat was first treated with albendazole (@ 10 mg/kg body weight, orally, single dose), and after 14 days, albendazole was administered in a double dose of the previous dose, and coprological examination was continued. As albendazole was found ineffective, levamisole was administered (@ 10 mg/kg body weight, orally, single dose), and the cat was intensively monitored by close inspection. Levamisole showed signs of toxicity and was not effective. After 14 days the cat was again treated with niclosamide (@ 20 mg/kg body weight, orally, single dose), and the cat was monitored in the same way, and coprological examination was conducted at day 0, day 7, and day 28.

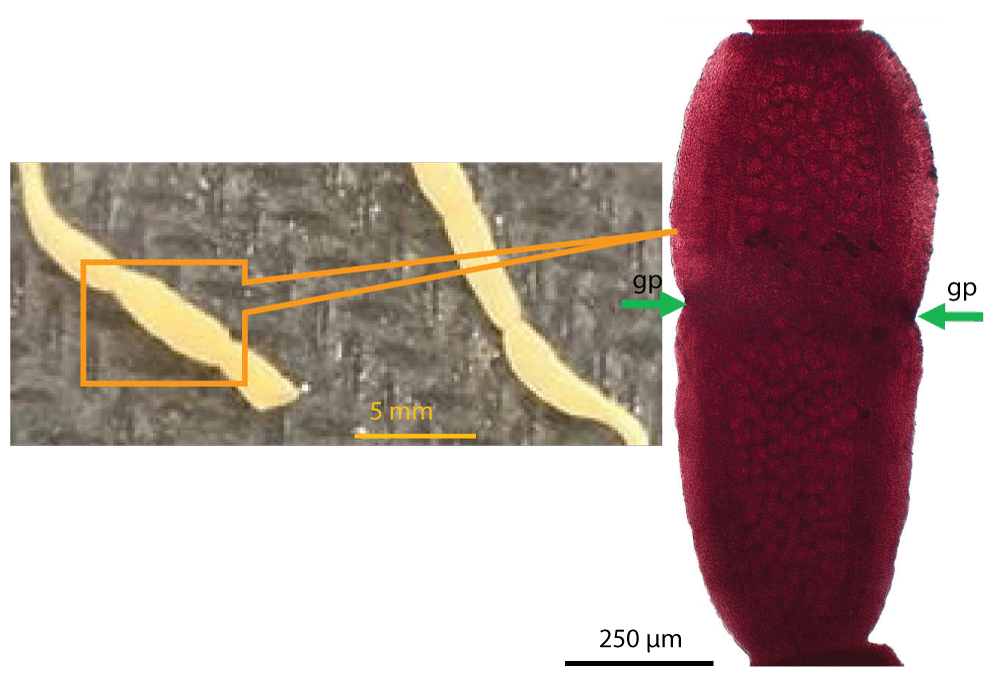

To identify the parasites, gravid segments were examined by preparing permanent slides. The stained segments were cucumber seed-shaped with two sets of reproductive organs, which open marginally (Figure 1), conforming to the morphological features of D. caninum [3]. Simultaneously, the cat was infested with flea, the intermediate host of the tapeworm [3]. The occurrence of D. caninum infection in cats has been reported previously [6-8]. As a treatment, the cat was medicated with commonly used anthelmintics, namely, albendazole and levamisole; however, the worm was refractory to both drugs even at the higher dose of albendazole. Additionally, levamisole showed toxicity, characterized by shivering and drooling of saliva; however, it was successfully managed. When the medication with albendazole and levamisole failed, we administered niclosamide and the cat stopped shedding of segments within a week. The cat resumed regular feeding and defecation. The cat’s owner was also advised to treat it with ivermectin (pour on) to make it free from flea. Taken together, niclosamide can be used to treat similar infections in animals. In vitro study can be conducted to validate further the efficacy of niclosamide on the worm.

Figure 1: Characteristic morphological features of the segment of Dipylidium caninum. (A) Gross appearance segment passed with feces. Gravid segments were separated from feces and washed with normal saline. (B) Microscopic features of the segment of Dipylidium caninum. Segments were collected, processed and stained with Semichon’s Carmine, and examined under a microscope using x10 objective. gp, genital pore.

- Taylor MA., Coop RL, Wall RL. Veterinary parasitology. Wiley-Blackwell. Oxford. 2007; 373–375.

- Yasuda F, Hashiguchi J, Nishikawa H, Watanabe S. Studies on the life history of Dipylidium caninum. Nippon Vet Zootech Coll Bull. 1968; 17: 27-32.

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. Bailliere Tindall. London. 1982; 763–766.

- Ramana KV, Rao SD, Rao R, Mohanty SK, Wilson CG. Human dipylidiasis: a case report of Dipylidium caninum infection from Karimnagar. Online J Health Allied Sci. 2011; 10: 28.

- Narasimham MV, Panda P, Mohanty I, Sahu S, Padhi S, et al. Dipylidium caninum infection in a child: a rare case report. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013; 31: 82–84. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23508438/

- Ash LR. Helminth parasites of dogs and cats in Hawaii. J Parasitol. 1961; 48: 63-65. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13862798/

- Wilson-Hanson SL, Prescott CW. A survey for parasites in cats. Aust Vet J. 1982; 59: 194. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7168726/

- Baker MK, Lange L, Verster A, Van der Plaat S. A survey of helminths in domestic cats in the Pretoria area of Transvaal, Republic of South Africa. Part 1: The prevalence and comparison of burdens of helminths in adult and juvenile cats. J S Afr Vet Ass. 1989; 60: 139-142. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2634770/